Rulemaking Petition Pursuant to the Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable Act (HFIAA)

We are scholars of securities law and financial economics whose research led to the development and passage of the Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable Act (HFIAA or the Act).[1] Our joint work, Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable, first identified risks that investors face from insider trading at foreign firms listed in the United States.[2] Using a unique dataset, we estimated that foreign-firm insiders traded to avoid losses of over $10 billion. The evidence shows that opportunistic trading has been concentrated in companies domiciled in nonextradition countries beyond the reach of U.S. law—especially China.

We respectfully submit this rulemaking petition pursuant to Rule 192(a) of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Rules of Practice to ask that the Commission develop rules to give investors the insider-trading transparency at foreign firms that Congress and the President have mandated under the Act.

While trading of corporate insiders at a U.S.-domiciled public company is subject to rapid disclosure under Section 16(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the SEC exempted foreign private issuers (FPIs) from that requirement.[3]As highlighted in our testimony before the Senate and the SEC’s Investor Advisory Committee, the SEC exempted FPIs from Section 16 long before China-domiciled companies became prominent among U.S.-listed foreign issuers.[4]

The Act eliminates that exemption, shining light on opportunistic trading in foreign companies that can harm American investors. In response, the SEC’s Staff issued a press release suggesting that the Act leaves in place an exemption for large FPI shareholders from disclosures otherwise required under Section 16.[5] The result of the Staff Press Release’s interpretation would be that large shareholders of U.S.-listed, Chinese-domiciled firms could avoid disclosing their trades to the public, while such disclosures would be required for shareholders of U.S. companies. Our petition instead urges the Commission to proceed as follows:

- First, rather than narrow the reach of an Act of Congress by way of a Staff press release, the Commission should initiate a prompt HFIAA rulemaking. The Act raises several important interpretive and practical questions that should be decided transparently by the Commission itself, not through informal Staff communications.

- Second, the suggestion in the Staff Press Release that the HFIAA does not extend Section 16(a) reporting to beneficial owners of more than ten percent of an FPI’s equity securities makes little sense. That claim is inconsistent with data we present below from Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable, inconsistent with clear policy considerations that motivated the Act’s passage, and inconsistent with the text of the Act itself. At a minimum, if the SEC is to take this view, it should do so through considered, Commission-level action, not Staff-level guidance.

- Third, the HFIAA authorizes the Commission to exempt a person or security from the Act’s requirements only if the “Commission determines that the laws of a foreign jurisdiction apply substantially similar requirements to such” person or security. We identify three considerations that should inform Commission determinations as to whether a foreign jurisdiction’s insider-trading disclosure rules are “substantially similar” for purposes of the Act and hence warrant an exemption.

I. The Need for Prompt Commission Rulemaking.

While we understand the press of the SEC’s regulatory agenda and its limited resources, the Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable Act presents the unusual case in which prompt Commission-level rulemaking is both necessary and justified. For three reasons, we urge the Commission promptly to initiate an actual HFIAA rulemaking—rather than interpret the Act by way of informal communications like the Staff Press Release.

First, the Act requires it. Section (d)(1) of the Act requires, “[n]ot later than 90 days after [December 18, 2025], the Securities and Exchange Commission shall issue final regulations . . . to carry out the amendments” prescribed by the HFIAA, so the SEC must initiate rulemaking quickly if there is to be adequate time for the notice and comment such rulemaking requires.

Second, as the Staff Press Release acknowledges, the terms of the Act make the SEC’s task unusually urgent. The reason is that, as practitioners have observed, the HFIAA is “self-executing,”[6] since it eliminates the FPI Section 16(a) Exemption as a matter of law on March 18. As a result, on that date, the Act will require the filing of the SEC’s Form 3 (for initial statements of beneficial ownership), Form 4 (for changes in beneficial ownership), and Form 5 (year-end disclosure) for all FPIs, and issuers who fail to meet that deadline may find themselves in violation of federal securities law.[7] In these unique circumstances, rather than risk widespread FPI noncompliance through inaction, the SEC should prioritize an HFIAA rulemaking.

Finally, the case for prompt rulemaking is especially strong because, as both the Staff Press Release and practitioners acknowledge, guidance is necessary for FPIs to comply with the HFIAA by March, and substantive questions require attention. For example, the marketplace would benefit from a Commission-level statement that FPIs must identify officers and directors—including directors by deputization—in the fashion long required under Section 16 rather than, for example, the law or customs of the issuer’s home jurisdiction.[8]

The Act’s deadline can be met if the SEC acts promptly. Nevertheless, the Staff Press Release gives rise to the worrying possibility that important questions related to the scope of an Act of Congress will be decided not through Commission-level rulemaking reflecting public comment but by informal staff-level press releases. That would be especially troubling with respect to the interpretive and exemptive questions we identify in this rulemaking petition.

II. Application of Section 16(a) to Ten Percent Beneficial Owners.

As scholars whose work helped guide, and who consulted with, Congress in connection with the Act’s development, we were surprised that the Staff Press Release suggested agreement with some practitioners’ view that the Act does not apply Section 16(a) to holders of ten percent or more of an FPI’s securities.[9] That view is inconsistent with the evidence we presented to Congress on this subject, the economic considerations that motivated the Act’s passage, and the Act’s text and structure. If the SEC is to take this controversial view, it should do so with care.[10]

To begin, the evidence shows that ten percent holders engage in especially opportunistic trading at FPIs. In Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable, we “examine[d] how the trading of foreign insiders compares to that of U.S. insiders” and provided data that “corporate insiders associated with Chinese and Russian companies listed on U.S. exchanges appear to trade in a highly opportunistic and abusive manner,” and the “SEC’s decision to exempt these insiders from Form 4 reporting requirements prevent[ed] market forces from disciplining their trading.”[11]

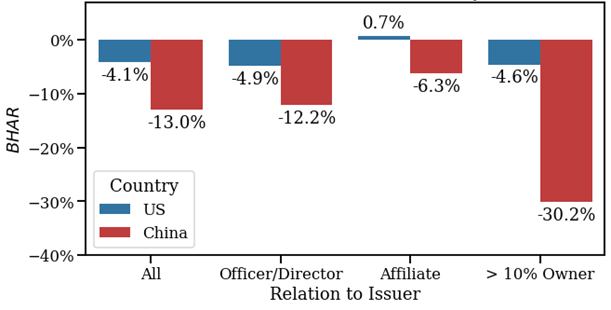

Drawing on the data and measures we used in Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable, Figure 1 provides evidence on median one-year stock returns at U.S.-listed, China-domiciled firms after stock sales by officers and directors, affiliates, and greater than ten percent owners:[12]

Figure 1. Opportunistic Trading at Chinese Foreign Private Issuers.

As Figure 1 shows, greater than ten percent owners avoid the largest losses in percentage terms through their stock sales. The median return following a stock sale by a ten percent or greater owner in a U.S.-listed Chinese company is –30.2%. That loss avoidance is larger than that at U.S. companies (–4.6%), and larger even than that for officers and directors at U.S.-listed Chinese companies (–12.2%).

Evidence shows that excluding greater than ten percent owners from the Act’s reach would continue to expose American investors to the risk that their investment dollars will be expropriated by large, controlling stockholders in Chinese FPIs. It is hard to see why Congress––motivated by a study showing that the “SEC’s decision to exempt” traders “from Form 4 reporting requirements prevent[ed] market forces from disciplining their trading”––would pass an Act that continues to allow large stockholders in Chinese FPIs to avoid those requirements.[13]

Nor is that view easily squared with the Act’s text. The Act’s title, as enacted, is: “DISCLOSURE BY DIRECTORS, OFFICERS, AND PRINCIPAL STOCKHOLDERS.” As Chief Justice Marshall explained centuries ago, while the “title of an act can[not] control” “[w]here the intent is plain,” when it comes to “removing ambiguities,” “the title [of a statute] claims a degree of notice and will have its due share of consideration.”[14] Congress would be surprised to learn that it enacted a law entitled, “DISCLOSURE BY . . . PRINCIPAL STOCKHOLDERS” yet did not change the law governing disclosure by principal stockholders.

Practitioners who take the view that this language does not extend the filing requirement to 10 percent or greater holders contend that HFIAA’s amendment to Section 16(a) “expressly references officers and directors—not holders of more than 10% of securities.”[15] That’s true, but the existing statutory language does refer to 10% holders. That language says that “[e]very person who is” an owner of “more than 10% of any class of any equity security (other than an exempted security) which is registered” “or who is a director or an officer” must disclose. So the central question is whether an FPI’s equity securities are exempted from Section 16.

About that question, the Act leaves little doubt. Section (c) of the HFIAA says that if “any provision” of the SEC’s Rule 3a12-3(b), containing the FPI Section 16(a) Exemption, “is inconsistent with the amendments made” by the HFIAA, that regulation “shall have no force or effect” as of the Act’s effective date. The text of Rule 3a12-3(b) in turn says:

Exemption from sections 14(a), 14(b), 14(c), 14(f) and 16 for Securities of Certain Foreign Issuers. Securities registered by a[n FPI] shall be exempt from sections 14(a), 14(b), 14(c), 14(f) and 16 of the Act.

All agree that this regulation is altered by the HFIAA; the question is how. To answer that question, note that the Rule addresses two issues—securities exempted and sections from which they are exempted—and makes no mention of who is required to file any required disclosures (a director, officer, or ten percent holder). To reach practitioners’ view, one would have to conclude that the Act does the following violence to the Rule’s language, naming for the first time the subject of a disclosure in a rule about exemptions of securities, not shareholders:

Exemption from sections 14(a), 14(b), 14(c), 14(f) and 16 for Securities of Certain Foreign Issuers. Securities registered by a[n FPI] shall be exempt from sections 14(a), 14(b), 14(c), 14(f) and 16 of the Act, except that directors and officers of issuers of such securities shall be subject to Section 16(a) of the Act.

Far less work is needed to reach the conclusion that, working from existing statutory and regulatory text, Congress extended Section 16(a) to ten percent holders. All that would need to change in the SEC’s existing Rule 3a12-3(b) to achieve Congress’s intent is the following:

Exemption from sections 14(a), 14(b), 14(c), 14(f) and 16 for Securities of Certain Foreign Issuers. Securities registered by a[n FPI] shall be exempt from sections 14(a), 14(b), 14(c), 14(f) and 16(b-g) of the [Securities Exchange] Act.

It is a well-known, “traditional interpretive canon that Congress is presumed to be aware of existing law and federal regulations when it legislates,” so much so that “any reasonable understanding of [a] statute’s effect requires awareness of the preexisting legal regime.”[16] Accordingly, courts interpreting the HFIAA will presume that Congress knew that Rule 3a12-3 exempts securities, not shareholders, from Section 16, and mandating that such exemptions “shall have no force or effect” meant that FPI securities would not be exempt from Section 16(a).

In sum, the evidence, economic policy considerations, and text that Congress chose all point towards the Act’s application to ten percent or greater beneficial owners of FPIs. Whether the SEC itself could reach a contrary construction in an interpretation that would survive judicial review is debatable—but it is clear that, in light of the arguments above, adopting that view by way of staff-level guidance will be unpersuasive to Congress, commentators and courts alike.

III. Relevant Considerations for Exemption.

The Act provides the Commission with “[a]uthority” to “exempt” “any person, security, or transaction, or any class or classes of person, securities, or transactions” from the HFIAA if “the Commission determines that the laws of a foreign jurisdiction apply substantially similar requirements to such person, security, or transaction.” While practitioners have told clients that they are now in private “discussi[ons] with the SEC about how it might exercise” this authority, we ask the Commission instead to do so in formal rulemaking subject to notice and comment.[17]

To begin, the Act’s “substantially similar” language has ample precedent in the SEC’s organic statutes and rules, where the phrase is understood to mean that the compared regime must be “at least as comprehensive” as the baseline.[18] And since, as explained above, Congress is presumed to be aware of existing federal regulations when it legislates, the use of this phrase in the Act indicates that the SEC should approach its meaning similarly. Accordingly, an SEC proceeding considering exemptions from the Act requires a Commission-level determination that the “laws of [the] foreign jurisdiction” are “at least as comprehensive” as Section 16(a). There are at least three dimensions the Commission should consider in conducting such an analysis.

Timing. First, the Commission should consider how quickly insiders must disclose their trades under the foreign jurisdiction’s law. Certainly, Congress thinks that subject important, having amended U.S. law two decades ago to require reporting within two business days. The financial economics literature offers evidence of a reduction in opportunistic trading after Congress took that action.[19] Thus, whether a foreign jurisdiction’s insider-trading disclosure rules provide “substantially similar,” or “at least as comprehensive,” investor protections as Section 16 depends in part on how quickly insiders must disclose under those rules.[20]

Language. Second, the SEC should consider whether the foreign jurisdiction’s law requires disclosures in the English language. Here, too, the importance of that characteristic to Congress is clear: the text of the statute itself mandates that FPI disclosures under Section 16 be “in English.” If American investors must process disclosures under another jurisdiction’s law, receiving the information in a foreign language puts U.S. investors at an information-processing disadvantage.[21] It is hard to see how that result would be consistent with Congress’s intent.

Electronic disclosure. Finally, a determination of whether a foreign jurisdiction’s insider-trading disclosure rules are “substantially similar” to Section 16(a) should require analysis of whether the jurisdiction mandates electronic filing. Again, the Act itself specifies that FPI filings made under the amended Section 16 must be made “[e]lectronically.” And as the Commission has recognized in recent rulemakings, filings that must be made electronically reduce investors’ “difficul[y in] us[ing the] disclosures.”[[22] Whether a foreign jurisdiction’s insider-trading disclosure rules are “at least as comprehensive” as the SEC’s Section 16(a) rules depends in part on whether investors can access the disclosures easily and electronically.

To be sure, we do not suggest that any of these factors should be decisive. Instead, these considerations may be weighed, among others, as the SEC considers exercising exemptive authority under the Act. Market participants should understand the methods the SEC intends to use to do that work and any other jurisdiction-specific characteristics the SEC thinks relevant. That is why a formal rulemaking with time for notice and comment, rather than informal Staff discussions and guidance, is the appropriate process for implementing the Act.

* * * *

For the reasons given above, we urge the Commission promptly to initiate a rulemaking project to implement the HFIAA in a fashion reflecting Congress’s mandate that American investors be given transparency on opportunistic trading in the securities of foreign firms.

1 Section 8103 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2026, S. 1071—1121-22 (Dec. 18, 2025) [hereinafter HFIAA or the Act]; see also David Lynn, House-Passed Defense Spending Bill Would Require Section 16 Reporting by FPI Insiders, TheCorporateCounsel.Net (Dec. 11, 2025) (“The bill [is] intended to address trading abuses identified by former Commissioner Robert Jackson (now at NYU law school) and” “professors Bradford Levy and Daniel Taylor” (quoting Alan Dye, Section 16.Net)). Bradford Levy is Assistant Professor of Accounting and Applied AI at the University of Chicago School of Business. Robert Jackson is Nathalie P. Urry Professor of Law at the New York University School of Law and Co-Director of its Institute for Corporate Governance and Finance; he previously served as an SEC Commissioner. Daniel Taylor is the Arthur Andersen Chaired Professor at the Wharton School and Director of the Wharton Forensic Analytics Lab. We write solely in our individual capacities; our institutional affiliations are provided for identification purposes only.(go back)

2 Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Bradford Lynch-Levy & Daniel Taylor, Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable, 70 Mgmt. Sci. 4167 (2024); see also Liz Hoffman & Tom McGinty, Chinese Executives Sell at the Right Time, Avoiding Billions in Losses, Wall St. J. (April 5, 2022) (“[I]n the early 1990s, in part to entice foreign companies to list on U.S. exchanges, regulators exempted [foreign firms’] executives and major shareholders” from rules requiring disclosure of insider trading); Ryan McMorrow, Eleanor Olcott & Andy Lin, How China’s Tech Bosses Cashed Out at the Right Time, Fin. Times (Nov. 6, 2021).(go back)

3 17 C.F.R. § 240.3a12-3(b) (“Securities registered by a foreign private issuer” “shall be exempt from” “[S]ection[] 16 of the Act” [hereinafter the Foreign Private Issuer (FPI) Section 16(a) Exemption]. The FPI Section 16(a) Exemption was adopted just over a year after the creation of the Commission itself, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Rel. No. 34-412 (1935) [hereinafter 1935 Release], in a rulemaking observing that the “Section 16 could have but a very limited field of application to the securities of foreign issuers [because] few foreign corporations have stock listed on American exchanges, and even in such cases the principal market is rarely in this country,” id.(go back)

4 U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Rel. No. 33-11376, No. S7-20250-01, 90 Fed. Reg. 24,232 (June 9, 2025), at 24,234-37 (concluding that, in 2023, the “most common jurisdiction of headquarters for [FPIs] was mainland China”) and citing, with respect to the FPI Section 16(a) Exemption, 1935 Release, supra note 5); H’rng Before S. Comm. on Banking, Housing & Urb. Aff. on Keeping Markets Fair: Considering Insider Trading Legislation (April 5, 2022) (testimony of Robert J. Jackson, Jr.) (“Our data provide systematic evidence that foreign-firm insiders avoid substantial losses by selling shares before stock-price declines.”); H’rng Before U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n Investor Advisory Committee, Foreign Private Issuers (Sept. 18, 2025) (testimony of Daniel Taylor).(go back)

5 U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Press Release, New Reporting Requirements Pursuant to Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable Act (Jan. 13, 2026) [hereinafter Staff Press Release].(go back)

6 See Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, Directors and Officers of Foreign Private Issuers Will Be Required to Report on Share Ownership and Trading with SEC (Dec. 17, 2025) [hereinafter Sullivan & Cromwell] (“[W]e read the operative provisions of the Act that make Section 16(a) applicable to directors and officers of FPIs as self-executing, meaning they will become effective without further SEC rulemaking.”); Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP, Section 16(a) Insider Reporting: Legislation Ends Foreign Private Issuer Exemption (Dec. 19, 2025) [hereinafter Cleary] (“Following the HFIAA’s enactment on December 18, 2025, officers and directors of FPIs will have 90 calendar days to file their initial Form 3, due March 18, 2026.”).(go back)

7 See, e.g., White & Case LLP, Directors and Officers of FPIs will be Subject to Section 16 Reporting Requirements (Dec. 19, 2025) [hereinafter White & Case] (“[C]ompanies should ensure they have the proper reporting systems in place” (citing U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, SEC Levies More Than $3.8 Million in Penalties in Sweep of Late Beneficial Ownership and Insider Transaction Reports (Sept. 25, 2024)); Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, SEC Insider Reporting Obligations Will Apply to Directors and Officers of FPIs (Dec. 18, 2025) [hereinafter Davis Polk] (“Violating Section 16 reporting rules can be embarrassing . . . and could trigger SEC scrutiny.”).(go back)

8 While FPIs were previously required to identify their officers under SEC rules, see U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Final Rule, Listing Standards for Recovery of Erroneously Awarded Compensation, 87 Fed. Reg. 73076-01 (Nov. 28, 2022), there is reason to expect that FPIs anticipating application of Section 16 to those individuals will “review this [prior] analysis,” since the “identity of such officers will now be publicly disclosed and more closely scrutinized,” Freshfields, Directors and Officers of FPIs to Make Prompt Public Disclosure to the SEC About their FPI Equity Holdings from March 2026 (Jan. 7, 2026), especially since the officer definition is famously flexible, Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Stock Unloading and Banker Incentives, 112 Colum. L. Rev. 951 (2012) (citing 17 C.F.R. § 240.16a-1(f) (an “officer” includes any “officer who performs a policy-making function, or any other person who performs similar policy-making functions for the issuer”)). We agree with commenters observing that “officer” “should be interpreted broadly,” to encompass “advisory, emeritus, or honorary directors, as well as” “corporate bodies” that “decid[e] policy issues” or “have access to material nonpublic information,” such that directors include any individual deputized by a shareholder to serve on the issuer’s board. Cleary, supra note 6.(go back)

9 Staff Press Release, supra note 5 (noting that “each director or officer” of an FPI “must file reports under Section 16(a) of the Exchange Act, pursuant to the Holding Foreign Insiders Accountable Act,” but not mentioning 10% holders). One firm, in an advisory authored by, among others, former SEC officials, originally opined that the Act amended Section 16(a) “to require directors and officers of FPIs and beneficial owners of more than 10% of an FPI’s equity securities” “to promptly disclose.” Freshfields, Baby It’s Cold Outside: Legislation Extends the Application of Section 16(a) to Foreign Private Issuers and Their Insiders (Dec. 12, 2025) (emphasis added). Days later, however, the same authors found that the same statute “does not clearly mandate reporting from the beneficial owners of more than 10% of an FPI’s equity securities” “and we [now] believe the best reading of Congressional intent from the text is that 10% owners are not covered.” Freshfields, Baby It’s Cold Outside: Legislation Extends the Application of Section 16(a) to Foreign Private Issuers and Their Insiders (Dec. 16, 2025) [hereinafter Revised Freshfields Interpretation]. With great respect to those authors, we think they had it right the first time.(go back)

10 We note, too, that practitioner views, even widely held ones, have not always been determinative of the meaning of the securities laws. While we expect that practitioners will urge the SEC to adopt this view, and that we and others will respond to those claims, here we argue only that those debates should be decided in public rulemaking proceedings, not SEC press releases. See John C. Coates IV, SPAC Law and Myths (Feb. 11, 2022), at 37 (describing “the main significance” of one recent “law firm statement” claiming to interpret securities law was “to show how . . . invested major law firms and their clients [were] in struggling to maintain the status quo”).(go back)

11 Jackson, Lynch-Levy & Taylor, supra note 2, at 4167.(go back)

12 These are mutually exclusive, self-reported categories drawn from the SEC’s Form 144. Returns are calculated over the twelve months after the sale, in excess of the US Total Stock Market Index, and MSCI China Index respectively. See id.(go back)

13 Id. That is especially true because the Commission’s rules defining an “officer” are famously flexible. Jackson, supra note 9, at 957 n.21 (quoting Peter J. Romeo & Alan J. Dye, Section 16 Treatise and Reporting Guide)). If the Staff Press Release’s view is correct, all a Chinese FPI need do to avoid disclosing an influential insider’s trades is to “review [its] prior analysis” of a large shareholder’s officer status and rearrange its internal affairs such that the insider is no longer an officer that “review.” Freshfields, supra note 8.(go back)

14 United States v. Fisher, 6 U.S. (2 Cranch) 358, 386 (1805).(go back)

16 Juan Antonio Sanchez, P.C. v. Bank of South Texas, 494 F.Supp.3d 421, 437 (S.D. Tex. 2020).(go back)

17 Davis Polk, supra note 7; see also Sullivan & Cromwell, supra note 6 (“We are liasing with the SEC further on the potential for jurisdiction-specific exemptions.”).(go back)

18 See, e.g., U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Final Rule, Covered Securities Pursuant to Section 18 of the Securities Act of 1933, 63 Fed. Reg. 3032-01 (Jan. 21, 1998) (“Additionally, the Commission interpreted the substantially similar standard to require . . . standards at least as comprehensive as those” the Commission was comparing exchange listing standards to) (citing the use of the phrase in the National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-290, 110 Stat. 3416 (Oct. 11, 1996)).(go back)

19 Section 403(a), Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745; Francois Brochet, Information Content of Insider Trades Before and After the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, 85 Acct. Rev. 419 (2010).(go back)

20 Consider, for example, the timing governing Israel’s insider-trading disclosure rules, which in practice require electronic disclosure of certain insider transactions either immediately or by the next business day. See Securities Regulations (Periodic and Immediate Reports), 5730-1970, reg. 36 (Isr.) (requiring immediate reports).(go back)

21 See, e.g., Yin-Siang Huang et al., The Effect of Language on Investing: Evidence from Searches in Chinese versus English, 67 Pac. Bas. Fin. J. 101553 (2021) (describing a “local language” information-processing effect for investors); compare 17 C.F.R. § 232.306(a) (providing, subject to certain exceptions, that “all [SEC] electronic filings and submissions must be in the English language”).(go back)

21 U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Final Rule, Updating EDGAR Filing Requirements and Form 144 Filings, No. 33-11070, 87 Fed. Reg. 35393, 35396 (2022) (“One commenter stated that the importance of the information contained [in a previously paper-filed form was] demonstrated by . . . third-party vendors that regularly visit the [SEC] reading room to scan [filings for] clients that pay for the information” (citing Ltr. to Vanessa Countryman, Sec’y, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n from David Larcker, Bradford Lynch & Daniel Taylor (March 10, 2021)).(go back)

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.